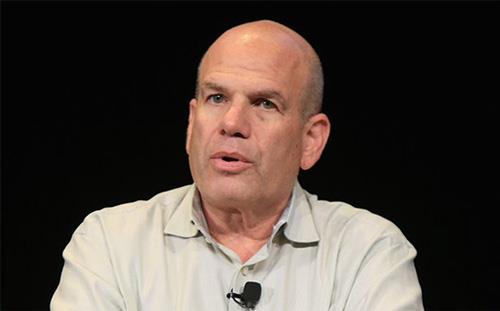

EDITOR'S NOTE: Our latest Guest Contributor is Andreas Halskov, an external lecturer in Film and TV Studies and a curator of screenings of historical films at the two biggest arthouse theaters in Denmark. In addition, he has written numerous books on film and TV (e.g., TV Peaks, University Press of Southern Denmark, 2015), is an editor of the scholarly film journal 16:9, and a regular contributor to CST. Andreas recently interviewed creator/writer/producer David Simon and is sharing it with TVWW.

"David came in, and what you had was long-form storytelling. Characters that were nuanced, stories that were nuanced, that required your attention and required you to follow it. Nothing was wrapped up at the end of one episode or one hour. It continued. It was sort of like a novel.

People look at television, and you see the lead character, and you think that's the protagonist. But I think, for David, the protagonist is actually America. American society is always the protagonist."

– Michael Potts, actor, The Wire (below right) and Show Me a Hero

We all know the story: An external force is threatening to eliminate the world and disturb the social order, as we know it. A strong man is put on the case and uses his will and agency to overcome the external threat and his inner conflict before restoring order and our collective faith in society and humankind. The typical Hollywood film follows a fairly well-known formula. It has a clear and well-defined plot, follows a straight corridor, and takes few excursions on the way toward the happy ending at the end of the corridor. It has a strong protagonist at the center of the story – a character who is promptly introduced and who sets the plot in motion, which then unfolds as a neat series of causes and effects. This principle of individualized causality is seen in most Hollywood films, and many of these principles are also apparent in the serialized fiction that we see on American television.

We all know the story: An external force is threatening to eliminate the world and disturb the social order, as we know it. A strong man is put on the case and uses his will and agency to overcome the external threat and his inner conflict before restoring order and our collective faith in society and humankind. The typical Hollywood film follows a fairly well-known formula. It has a clear and well-defined plot, follows a straight corridor, and takes few excursions on the way toward the happy ending at the end of the corridor. It has a strong protagonist at the center of the story – a character who is promptly introduced and who sets the plot in motion, which then unfolds as a neat series of causes and effects. This principle of individualized causality is seen in most Hollywood films, and many of these principles are also apparent in the serialized fiction that we see on American television.

These characteristics, however, are not typical of the fictional stories by TV creator and showrunner David Simon, who began his career as a journalist and who helped define the so-called "Golden Age" (aka "Platinum Age" according to our own David Bianculli) of cable television at the turn of the century. Through lauded TV classics like Homicide: Life on the Street (NBC, 1993-1999), The Corner (HBO, 2000), The Wire (HBO, 2002-2008), Generation Kill (HBO, 2008), Treme (HBO, 2010-2013) and The Deuce (HBO, 2017-2019), Simon has come to define a pivotal shift in American television, largely by going against the grain of American politics and traditional formulas known from Hollywood and American television.

The Past as a Mirror

AH (Andreas Halskov): I know that you are working on two different shows at the moment, and both of them are essentially period dramas. Could you tell us about the miniseries that you are editing as we speak?

DS (David Simon): The story is based on a novel by Philip Roth called The Plot Against America. It is an alternative history of America, based around the election of 1940 that was premised on the idea that instead of Franklin Roosevelt being elected on the dawn of World War II, America elected an isolationist Republican in the form of Charles Lindbergh, the aviator, who historically was, in fact, pro Nazis and also violently anti-Semitic as well. And, so, he brings America in on the side of strict neutrality while, at the same time, supporting Hitler. It was an artifact when it was published in 2004. Roth was writing with the election of George W. Bush in mind and some degree of populism as being a rallying point for American politics. Obviously, in the wake of the election of Donald Trump, it has gotten a greater significance, so we optioned the book, and HBO is making it into a miniseries that will be out in March next year.

AH: Like The Deuce and Show Me a Hero (right), your forthcoming miniseries looks to the past in order to speak about the current political climate. Sometimes, period dramas seem like nostalgic glances into the past, but you seem to use the past as a sort of mirror. Is that the idea?

AH: Like The Deuce and Show Me a Hero (right), your forthcoming miniseries looks to the past in order to speak about the current political climate. Sometimes, period dramas seem like nostalgic glances into the past, but you seem to use the past as a sort of mirror. Is that the idea?

DS: Absolutely. There's no point in doing period drama if you're not reflecting on the world that currently exists. The problems of a hyper-segregated society and inequality are even more profound today than they were at the time of Show Me a Hero. The same things are going on in every city about what to do with the poor, where to put the poor. There's a dearth of affordable housing. The city is a playground for the rich and hell for the poor. So there is nothing being said about Yonkers in the 1980s in Show Me a Hero that can't be applied now to our current society.

Similarly, The Deuce is about misogyny, sexual commodification, and labor, and gender, and those topics are still relevant. The status of women in society is being questioned as aggressively today with #metoo and #timesup as it ever has been. The same arguments are still unresolved. So, if you're not speaking of the present, you've got no business accessing the past.

The Structural Focus

Before Show Me a Hero and The Deuce, David Simon created one of the most significant and popular TV series of the 2000s – a piece which is often placed at the tops when critics and reviewers are asked to list the best TV shows of all time. I am naturally referring to The Wire, which differed markedly from other quality shows of its time by focusing on environment rather than plot, structures rather than powerful individuals, and by changing the setting and the focal points with each season.

AH: What's interesting about The Wire, as I see it, is that it explores the problematic structures and failed institutions in the USA, instead of focusing on strong individuals and immediately exciting plots. It was a groundbreaking show, and it has been described as neo-realism, sociology, a systemic critique of America, and many other things. How do you see it?

DS: It's a critique of why we can't solve any of our problems nationally. There are problems that have to do with how we live together, and how we live together in the 21st century is inevitably an urban question. Urbanity is now the future of humankind, and the shape and structure and viability of the city is going to determine whether or not we survive as a species. In that sense, we're using the city allegorically to make arguments about what has gone wrong with our society that our institutions no longer perform or even attempt to perform as they once did and how problems and even the attempts to solve problems become more and more elusive – and why the center of our society, which used to be some communal sense of responsibility, can no longer hold.

We've done seven pieces now for HBO, and we're about to cut together an eighth, and they're all about structure. They're all about the systemic. And that has to prevail for us to care about it.

And one of the reasons we found that to be a plausible pursuit is that we're doing long-form. We're doing long-form television shows. We're doing miniseries and series, so there's time to lay out the structural critique.

AH: Many people have pointed to The Wire (right) as central to the so-called Golden Age of cable television. What precipitated that shift in American television?

AH: Many people have pointed to The Wire (right) as central to the so-called Golden Age of cable television. What precipitated that shift in American television?

DS: American television was a juvenile form in fundamental ways until there were some channels that could get rid of advertising and commercials as the revenue stream. When they were the revenue stream, you could not present a story that was particularly dark or disturbing or problematic or argumentative in a political sense because it disturbed the consumer class. It disturbed the dynamic between the advertiser and the consumer. It didn't put anyone in the mood to buy cars or blue jeans or iPods or anything. But once you got rid of the advertisers and made it a subscription model, now you started having grown-up stories.

AH: Many people have also pointed to the level of attention and patience that a show like The Wire requires. I guess we could say the same thing about Treme.

DS: I'm particularly proud of that one, actually, in that it avoids, it denies itself, all of the tropes and metrics by which American television usually measures itself. It only has enough violence to depict the actuality of violence in the city. It only has enough sexuality to accurately chronicle the lives of ordinary people. It's not trading on the things that make television shows go forward. It's a lot harder to get people to watch a show where you put a trombone in a guy's hand than if you put a gun or a blonde, and we were determined to say something, again, about the American city. What in urbanity matters? What is resilient? What must endure? Treme is a show about culture. It's about the culture of a city that's steeped in culture, and it survives only because of culture. It was an attempt to make an argument for the city.

American Neo-realism

AH: I have always seen your TV series as a serialized and modernized version of Italian Neo-Realism – a movement which was recognized for its use of location shooting, open-ended and decentralized stories, and amateurs who speak in the vernacular. The ideas behind the Neo-Realist movement were formulated by the writer Cesare Zavattini who claimed that all good movies depict "the pressing issues of their time." To me, that line could almost be a dictum of your work. Would you agree with Zavattini?

DS: I would not be so limiting. I would say that's what my work has to be because my training is in journalism, not in film and certainly not in the entertainment industry. So what I'm chasing has some rooted logic in journalism, and journalism is about the issues of our time. From my point of view, this is all I know how to do, but I can certainly conceive of great art that targets not simply the social issues of our time, but maybe just the human condition in general. Or maybe I'm speaking in such generalities that those are always issues of our time. Shakespeare works, and the Greek plays work because man is man, and his nature is his nature, and the forms by which power and dignity ground themselves, through humanity or through the human condition, don't really ever change. The scale of hope and risk for human beings is the same for Hamlet as it is for Oedipus. This stuff works because we can watch Medea, and we can encounter her trauma through our own knowledge of domestic pain and gender. And it's not really of our time; it's of every time.