by Eric Gould and P.J. Bednarski

Throw the penalty flag at the NFL for "illegal formation" or "delay of game", but however you characterize it, the league's record on concussions and brain disease over the past 20 years hasn't been good, or timely.

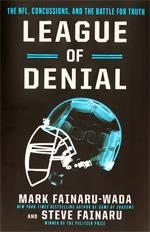

The errors, conflicting statements and stalling were all laid out Tuesday night on the PBS Frontline series in a two-hour documentary League of Denial: The NFL's Concussion Crisis.

Based on the book of the same name by ESPN writers and brothers Mark Fainaru-Wada and Steve Fainaru book, the two-hour documentary ran down a 20-year battle to come to grips with head injuries, starting with the death of former Pittsburgh Steelers center Mike Webster in 2002. Webster, a 17-year veteran of the head to head combat of an NFL lineman, began behaving erratically after he retired.

He couldn’t finish simple sentences, or communicate simple thoughts. In one scene, he is shown being interviewed about his playing day, and struggling—and ultimately failing—to make a coherent statement.

He was divorced and went broke and at one point he was living out of his truck. His son recalled that he was so out of it, he once revealed that it had become a process for him to remember that zipping his coat would warm him if he got cold.

He died suddenly at the age of 50.

Webster was the first NFL player to have his brain autopsied and it revealed evidence of chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE – a neurodegenerative disease. Ghoulish autopsy portraits also showed a 50-year old man who looked closer to 70, with a body misshapen and twisted after years of physical punishment.

Webster had been granted disability by the NFL for his mental incapacitation, with NFL doctors admitting in their report that his condition was caused by 17 years of impacts and concussions. But that report was not revealed to the public until years later.

League of Denial showed that report went unreleased, and after, other committee reports and medical papers went counter to that summary, arguing that there was no definitive evidence that concussions were the cause of brain diseases later in life.

From there, League of Denial marched through the unfortunate history of the study of concussions and the league's unwillingness to admit what seems obvious – that getting clocked an estimated 1,000 times a season for the average player might be a bad thing.

A generous portion of the documentary regards the lengths—obvious in the analysis of the filmmakers—the NFL took to deny research or misdirect it, and attempt to tarnish the reputation of medical researchers whose findings countered the white-washing of the league’s own concussion study committee.

Dr. Bennet Omalu, who made the discoveries about Webster and another player, was, by his accounting, viciously discredited by the league. Dr. Ann McKee, a leader of a Boston University CTE unit that began post-mortem studies of the brains of NFL players, relates how she was disregarded and condescended—she considered it sexism--when the league, surprisingly, asked her to address them.

She notes in the documentary that she has now studied the brains of 46 players, and 45 of them showed signs of damage. “We have an enormously high hit rate,” she says, noting that kind of “success” rate suggest a significant, overwhelming link between football and brain injury.

The core of the documentary correctly played out as a Watergate-style "What did the NFL know, and when did they know it?" with NFL studies on concussions going back to the mid-nineties being inconclusive either by design or by avoidance.

The league began to respond more proactively with rules to protect players from helmet-to-helmet contact around 2009. But that was only after league Commissioner Roger Goodell had been called before Congress to testify on the league's policy. Goodell would not acknowledge a connection between head injuries on the field and brain diseases like dementia and early onset Alzheimer's, commenting that it was for doctors to testify to medical facts, not him.

Rep. Linda Sánchez (D-Calif.) infamously said Goodell's remarks reminded her of tobacco company executives denying the health risks of smoking.

That remark by the congresswoman framed the problem in a way that resonated with the American public and shocked the NFL, which enjoys its position as “America’s game.”

It instituted more new rules to protect players, levying penalties and sometimes fines for tackles that once made up highlight reels for NFL Films. (Indeed, for years, a title sequence for “Monday Night Football” was two helmets butting together and then exploding. That kind of hit is a major transgression now.)

This year, the league also settled a class-action lawsuit by 4,500 former players claiming damages for traumatic brain injuries and disease and charging the NFL misrepresented the risk.

By avoiding a trial (players wanted over $2 billion) and settling for $765 million, the NFL put the problem behind it, for now, and without much pain to a business that grosses between $8-10 billion annually. The settlement was worded so the league still, officially, acknowledges no link between football and head injury.

Perhaps more rightly, League of Denial (now available online here) also pointed the finger at those who also looked the other way when players were going down – that would be us, the fans. The league's ratings and income started going through the roof in the 70s and it hasn't stopped since, with the NFL themselves getting into the TV business with its own NFL Network cable channel in 2003, giving fans 24-7 news, film and discussion.

As Steve Fainaru notes—as if we need to be reminded--it’s big, big business for television too. ESPN, he notes, pays over $2 billion for NFL rights, with games grossing $120 million a week in fees. “That’s like them making a Harry Potter movie week in and week out,” he says.

Years ago, in the 50s and early 60s, football had the goal posts, two steel columns and a cross bar, set on the goal line. Players were routinely knocked silly running into them at full-speed. Thick padding was added, and then the league just moved them to the back of the end-zone where no one could get hurt.

File under obvious as a steel post in your face.

Frontline seems to suggest the same clear danger about football itself. Near the end of the documentary, Dr. McKee says flatly she would not let a pre-teen play in a Pop Warner type league. Then, considering the stats about brain injuries in the NFL, she says, “I am really wondering if at some level, every single NFL player has this [brain damage].”

Change can’t happen without fan support. They'll have to demand a football culture based on its true merits - a team sport built on high-octane athleticism and the chess master-like brilliance of its quarterbacks and coaches that outwit the opposing army, not one where tackling means hitting the opponent into the next time zone, and maybe knocking them out of the game, and life, forever.

But for Americans raised on the thrill of violent clashes at the line of scrimmage, is that the game they want to see?